Saying “No” to $15,000,000

January 3, 2012

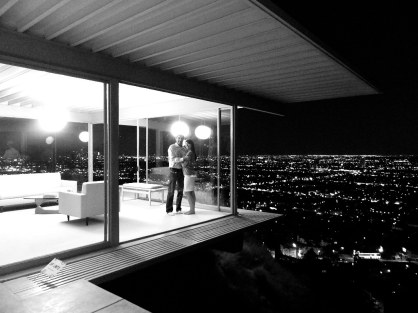

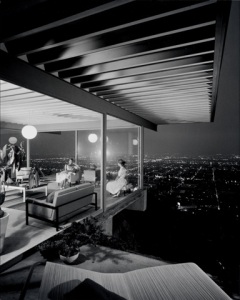

If you have ever looked book of modern architiecture or are familiar with the photographer Julius Shulman, the picture above may look familiar to you. Excepting for the fact that two young women (as seen in middle photo from 1960) have been replaced by my wife Kim and me, it was at this exact location where Shulman snapped the most iconic architectural photograph ever taken, 52 years ago.

Over the recent holiday Kim and I spent a few days in southern California and the central coast, wine tasting and looking for the sun. We found both in ample supply, and along the way we  found the time to tour this Los Angeles house – known as Case Study House #22 and still held by its original owners, the Stahls – and learn about it’s history, it’s current condition and it’s value.

found the time to tour this Los Angeles house – known as Case Study House #22 and still held by its original owners, the Stahls – and learn about it’s history, it’s current condition and it’s value.

In addition to the pleasures of the house, the tour and a remarkable sunset, we learned that the most recent valuation of the home was approximately $15 million dollars, and that offers of purchase are not uncommon. Although they no longer reside here, and while of course we are not privy to the details of their trust, the owners have never been interested in selling. Aside from docent-led tours and the occasional weekend visit by the Stahls, the house sits on its hillside, empty of occupants. Apparently, no amount of money can persuade the family to let it go.

This is not a story about architecture, or photography. It is about the real or perceived value of personal possessions: How is it that untold amounts of money do not always convince us to part with them? What does this say about the value of these connections, and how does this relate to the meaning they hold for us?

Understanding the power of that connection – for the Stahls and for each of us as well – can reveal much about the importance of what we use our money for, and about the inter-connectedness between the things we own, our values, our personal histories and the way we live our lives.

Move Over Honey… I’ll Drive

March 2, 2011

Do men and women invest differently? Do they achieve different investment results statistically? Is one gender more confident than the other in terms of money management?

Not that gender studies is an under-served discipline, but I believe it’s time we take a closer look at gender-based financial behavior.

It turns out there is much that separates the sexes where the dollar is concerned. Interestingly, there seems to be a disparity between the family balance sheet and the family investment account. A ShareBuilder Women and Investing study from 2007 found that just over 60% of women manage the household checkbook and 44% – versus only 23% of men – oversee the budget. However, only 15% of married women take primary care of the family investments, and only 12% of women – versus 21% of men – feel confident about their investment abilities.

Does this “confidence gap” account for better investment returns in portfolios managed by men? Of course not!

Not surprisingly, female investors do better on a number of levels, in spite of (or because of) the machismo of men on the subject. Surveys suggest that while men are more likely to chase so-called 5-star mutual funds and the hot stock du jour, women spend almost twice as much time researching before investing, and they have the results to show for it. Finance professors Brad Barber of UC Davis and Terrance Odean of UC Berkeley recently found that – although women hold less risky portfolios than men – they consistently achieve bigger returns.

Psychologists have long-held that men are more prone to over-confidence, so we might expect them to manage their portfolios more aggressively. An over-confident investor is far more likely to engage in excessive trading (costs reduce returns), to rely on market timing to guide them (never a good idea) and to shun the advise of an advisor. (No comment.)

But back to return. Barber and Odean found that married men trade 45 percent more than married women, yet they earn risk-adjusted returns that are 1.4% lower. Amongst the unmarried it gets even worse. Single men trade 67 percent more than single women but earn annual risk-adjusted returns that are 2.3% lower. Worse still, men in general trade far more than women, turning over 77% of their portfolios each year to 53% for women. (It seems men and women both need financial advisors.)

Whether or not these findings conform to popular gender stereotypes (men being more competitive; women more collaborative) is a matter of debate. In any case, if you are working with me take comfort; I am an outlier.

As for other areas of manly over-confidence, I will take the fifth.

Investment Resolutions For This (Or Any) Year

February 4, 2011

I decided to wait until everyone else had gone public with their New Year’s resolutions before identifying the list below. (Plus it took the entire month of January to compile these.)

Coaching clients to become better investors – essentially, investing within the larger context of ones goals and foregoing a reliance on economic forecasts and market predictions – is a constant challenge. People generally tend to respond emotionally to the ups and downs within their portfolios, which indicates just how important money is to most of us, or at least how deeply we are connected to it. When you add to this the effect of financial journalism (which is largely a form of entertainment and has nothing to do with the day-to-day performance of a mutual fund portfolio), it can be very difficult to stay focused or to remain rational.

With that in mind, here are ten “resolutions” which I hope will lead to good investment decisions this year and every year.

1. I will not invest based on a forecast, mine or anyone elses. I will recognize that the urge to form an opinion will never go away, but I won’t act on it because one cannot repeatedly predict the future. It is, by definition, uncertain.

2. I will not confuse entertainment with advice. I will acknowledge that the financial media is in the entertainment business and their message can compromise my long-term focus and discipline, leading me to make poor or irrational investment decisions. If necessary, I will turn off CNBC and turn on ESPN.

3. I will keep a long-term perspective and appropriately consider my investment horizon (i.e. the probable life-span of my portfolio) when determining my performance horizon (i.e. the time frame I use to evaluate the results).

4. I will continue to invest new capital when I can, because it is time in the market – and not timing the market – that matters.

5. I will adhere to my investment plan and continue to rebalance it (i.e. systematically buying more of what hasn’t done well recently) rather than unbalance it (i.e., buying more of what’s hot).

6. I will not focus my portfolio in just a few securities, or even a few asset classes, as diversification represents the best way to manage risk.

7. I will ensure that my portfolio is and remains appropriate for my goals and objectives.

8. I will manage my emotions by learning about and acknowledging the particular biases that influence my behavior.

9. I will keep my cost of investing reasonable, in order to improve bottom line results.

10. I will stop searching for tomorrow’s star mutual fund manager, as there are no gurus, and this year’s hot-shot may well be (and many times is) next year’s flop.

The Financial Planning Gap

February 1, 2011

Undertaking a process of financial planning is rarely a front-of-mind activity, nor one that many people approach with excitement or anticipation. As important as it may be to identify, assess and prioritize a list of financial objectives, the process can be a difficult and emotional one. And although the results of the process almost always provide a high degree of confidence about retirement planning and goal achievement, a large segment of pre-retirees simply haven’t bothered.

A recent study by the Society of Actuaries (how’s that for a place to take the kid’s on a Sunday afternoon) concluded in a recent survey that nearly half of baby boomers have no financial plans in place in case they live longer than expected.

So what accounts for this gap?

One reason could be the cost of financial planning. With many advisors charging between $1,000 and $3,000 to put together a comprehensive financial plan, it can be cost-prohibitive, although the cost of planning often pays for itself in the first year alone, in a variety of ways.

Another issue is the negative past experiences people have had with financial service providers. This typically has to do with high commissions sales reps, or with brokers who steered their clients into bad investments and never communicated effectively with them about their goals.

A third possibility is the fact that many people have not taken the time to explore their most important goals, many of which are directly connected to their savings and income.

Finally, I suspect that plain old procrastination is the primary culprit. Frequently a new engagement begins with the client telling me just how long financial planning has been on “the back burner” for them. Money can be a confusing, complicated and emotionally-charged subject, and for many it is easy to simply not face it. (“If I don’t go to the doctor, I won’t know what ails me.”)

In any of these cases, finding the right financial planner to work with and communicating clearly about what you want out of the process can go a long way toward helping you achieve your most important financial and life goals. Indeed, it is the number one responsibility of financial advisors to help their clients discover what these goals are.

My experience has been that once people are aware of their financial goals they become very interested in them, and once that happens, they are no longer resistant toward planning for their ultimate fruition .

The Family That Plans Together…

January 3, 2011

Last week had the pleasure of a first meeting with a young man (we’ll call him Jack) who represents the youngest generation in a family that I have been working with for seven years. While preparing for the appointment, it occurred to me that this was the first time in my career that this phenomenon had occurred. I have worked with siblings, formerly married couples, the elderly and their trustees, but never had I met individually with the first, second and third generations of the same family unit.

I wondered before the meeting, would I recognize Jack’s money values as being consistent with those of his parents and grandparents? Would there be a thread that linked the way each generation related to their money?

Our consultation couldn’t have been more basic: how best to allocate a moderate amount of cash into an investment portfolio which reflected Jack’s general profile, objectives and constraints. Upon reflection, I realized that I was moved less by the obvious inter-connectedness of the family than by the ways in which money linked them together, and for the good.

I have seen many examples of this: the transformation of an inheritance into a meaningful financial outcome for heirs and their families; a grandparent opening an educational account for their grandchild where the parents may not have had the means to do so; a family consciously budgeting for an annual vacation which the eventual adult children continue (using their own money); a child using the savings of her accumulated allowances to buy a gift for her parent.

What struck me as I listened to Jack outlining his financial goals and investment expectations was the uniformity of the approach to money between all three generations of his family. Money values that had originated with his grandparents, and which I had witnessed during conversations with his parents, were now being espoused by Jack, age 21.

Many in my profession are of the belief that the innocent money messages we receive as children are carried forward into our adult lives. A person given cash willy-nilly all their lives may never learn to save; the children of parents who are fearful of the stock market are usually less inclined to invest as adults; someone who witnessed their family suffering in the Great Depression may never be comfortable spending their money, no matter how much of it they have.

Conversely, a child who is taught to save their allowance and is rewarded for doing so can learn to appreciate the value of compound interest; a person who grows up being involved in family discussions about charitable giving sees the impact of money on the greater good; parents who educate their kids about the role of money in our society, both for good and otherwise, will likely produce adults with a broad understanding of money, who can then hopefully direct their own income and savings in a more well-rounded manner.

We may not be able to fully dictate the financial values our children carry into the world, but we most certainly can influence them, as I have now seen, first hand.

Expectations and the Economy

December 27, 2010

It’s amazing how the public’s expectation about the stock market and the economy seem to be influenced by whichever direction the markets happen to be performing at the time.

A recent study by Putnam Investments found that 61% of Americans believe that stock prices will rise in 2011, and that forty-three percent are betting on a better housing market. A third believe the economy “will be much healthier” in 2011, and 47% expect that “consumers will start to spend again.”

I can’t prove this statistically, but I’m willing to bet that in 2001, 2002, and 2008 (the last three calendar years the market was down) a majority of the same 1,000 survey participants would have predicted that the markets would continue to fall the next year and that the housing market would worsen. This is the nature of financial prognostication. When the economy is good and the markets are on the rise, we expect the trend to continue. Conversely, when the economy is in recession and the markets are down you hear comments like, ” I don’t see this improving for some time,” or, “I sold my equity funds and plan to stay in cash until the markets improve.” (Of course by the time they get back into the market most of the gains have already transpired but that’s another story.)

Not surprisingly, the head of global marketing at Putnam says that these results show that “despite the fact that this has been difficult year, Americans retain their essential optimism.” This may be true, and it would be a convenient explanation regarding the survey, but I suspect the results are more about psychology than optimism.

Distinguishing between “volatility” and “loss”.

November 1, 2010

The prolific Fidelity portfolio manager Peter Lynch once famously said that “the real key to making money in stocks is not to get scared out of them.”

As I write, the equity markets (as measured by the S&P 500) are enjoying year-to-date gains of around 6%, a modest yet welcomed result. The Nasdaq index is up over twice that amount, climbing just over 14% since the beginning of the year. (Less modest and more welcomed.)

Coming off the losses we experienced from October 2007 to March 2009, it’s certainly been a plus for those in my line of work and for the clients we serve to see the markets recovering some (not all) of those losses, no matter the stalled recovery and seemingly constant economic uncertainty.

Whatever the current condition of the market, it seems like a good time to acknowledge the fact that volatility – up or down – is a constant, while gain and loss will forever be taking turns acting upon client portfolios. Volatility itself has no bearing on whether or not we make or lose money within our portfolios. Selling determines that. Knowing this, it is important to distinguish between volatility and loss, and to reinforce the fact that they are not the same thing.

I would venture to say that clients of Milestone Financial typically have a higher-than-average level of acceptance concerning volatility; that is, they have been asked to identify the margin of volatility they can accept, knowing that, in general, for every tick up or down on the volatility scale there is a corresponding amount of gain or loss which they can expect when it comes time to sell. Setting an investment policy which relates (among other things) to “volatility”, clients tend to be more patient when portfolios experience a “loss”.

In any case, it may be useful to clients and non-clients alike to illustrate the loss-volatility distinction by way of Warren Buffett, who controls Berkshire Hathaway Inc: to wit: what result did three cataclysmic market events have on Berkshire Hathaway stock, and what was his response as an investor during each of them?

On October 19, 1987, the date of the single greatest one-day crash in stock prices in American history, Buffett’s personal shareholdings in Berkshire Hathaway declined by $347,000,000. That’s the amount he “lost” in one day.

But he didn’t sell, therefore he technically didn’t “lose” anything.

Then, between July 17 and August 31, 1998, he “lost” $6,200,000,000. Yes, that’s six billion, two hundred million dollars.

Still he didn’t sell.

Finally, between the October ’07 market top and the March ’09 bottom, Warren Buffett “lost” approximately $25 billion dollars. But of course, he didn’t sell even then.

When asked by a CNBC personality subsequent to March ’09 how it felt to have lost 40% of his lifetime accumulation of capital, his response was that it felt about the same as it had the previous three times it had happened.

Here’s the instructive part: during the period of time between the first and second of these events, Berkshire Hathaway stock grew from $3,170 per share to $60,500 per share. Between the second and third, the share price grew from $60,500 to $73,195. On October 29 2010 Berkshire shares closed at $119,300.

Granted, this is probably the most extreme example one could find regarding the negative correlation between loss and volatility, but that doesn’t make it a bad example, and it certainly doesn’t make it wrong.

The key to coping with volatility is to understand it in the context of loss. Volatility has been a constant in equity markets since there’s been equity markets, and it is here to stay. All by itself, volatility does not determine the amount or the severity of loss (or gain for that matter) of capital. For that to happen, investors must behave in certain ways. Reacting to volatility is natural. Indeed, it would be difficult not to have an emotional response to the decline in the value of your portfolio (especially a severe one) as most of us experienced over the last decade or so.

The challenge is to not react to volatility by abandoning the tenants that led you into the markets in the first place, but to recognize it as an inevitable part of the investment process. Volatility cannot be controlled, but our response to it certainly can.

Don’t Just Do Something… Stand There.

October 10, 2010

I was recently conducting a portfolio review with a newer client of mine when the subject of “activity” (or rather, “inactivity”) came up. The question was, why was her portfolio being managed in such a seemingly passive way? Shouldn’t we doing in more trading, buying and selling or exchanging of funds? (My quick response was that as a matter of policy our firm takes the time to select mutual funds early in the planning process that are well matched to the client, and which properly diversify the portfolio from the beginning. Then we leave it alone. But it is an important question and one that I would like to elaborate on here.)

In the case of this particular client, we were looking at a portfolio that engages in significantly less risk than the market overall, and yet the year-to-date return of her portfolio was only nominally under-performing the S&P 500 index of stocks. How could it be, she asked, that a portfolio consisting of only 55% stocks could essentially match the performance of the total stock market, during a period of time when the stock market had risen?

Let’s start with a distinction. There are two kinds of behavior when it comes to investing: investment behavior, and investor behavior. (I suppose there is also advisor behavior, market behavior and economic behavior, but we’ll leave those for another time.) Investment behavior refers to the performance of a particular stock, mutual fund or funds, or how a particular fund has done over a given time period. By contrast, investor behavior relates to the performance of the person who invests in that fund or group of funds; in other words, to the performance of her portfolio over time as she buys and sells and exchanges from one fund to another.

Luckily, there is a quantifiable way to draw this distinction, one which contrasts the results of actively traded portfolios with more static, buy-and-hold type of portfolios.

Enter Dalbar, a leading edge investment research and communications firm which has been examining this distinction since 1994, measuring the effects of investor decisions to switch into and out of mutual funds over both short and long-term time frames. The results consistently show that the average investor earns less – in many cases, much less – than the mutual fund performance of the funds they invest in.

Results of sixteen years of studies has yielded two assumptions: 1) investment results are more dependent on investor behavior than on fund performance, and 2) mutual fund investors that hold onto their funds are more successful than those who attempt to time the market, over each of the 20-year periods examined.

How much more successful? For the period ending 12/31/2009, the S&P 500 returned 8.10% for the last 20 years (the 1990′s and 2000′s). Over this same time period, the average equity investor just barely beat inflation (2.8%) with an annualized return of only 3.17%. Thus, the premium on return for investors who simply chose a fund stayed with it (rather than buying and selling and chasing returns) was around 5%. What does that mean? Well, on a $100,000 investment, a portfolio earning 3.17% annualized over 20 years becomes $186,667, while the same amount earning 8.10% grows into $474,803. That’s an extra $288,136 for buying a mutual fund and then looking out the window for the next 20 years. And when you factor in that there are equity funds that periodically outperform the S&P 500, the results can be even more pronounced.

What drives investors toward inappropriate behavior? What leads them to believe that they can out-smart and out-perform the market?

For many, investing is a hobby, and as such lends itself to over-activity for the sake of activity. For others it may be more about self-deception; the belief that unlike most everyone else they can successfully exploit information and consistently beat the market, despite mountains of evidence to the contrary. (The fact that they may be beating the market during smaller, random time periods may only succeed in building an unrealistic sense of accomplishment.) For others still, it is perhaps the notion that to do well you should be doing something… shouldn’t you?

It is those using this last rationale that stand to benefit most from the Dalbar studies. For these investors the results are more than instructive, for they reinforce behavior that has been shown again and again to lead to better investment results over time.

That certainly won’t be enough to sway every investor, but you can’t blame me for trying.

Can Money Buy Happiness? (If you make close to $75,000 a year, yes, it can.)

September 21, 2010

Does money buy happiness? We all have our own answers to this commonly contemplated question, depending not only on our incomes but also on our individual histories and the meaning of money in our lives. The question of whether money buys happiness is actually many questions at once: How do we assess our happiness in general? By what means do we make use of our money and how does this correlate to our sense of well-being? What was the role of our parents’ money in our childhood experiences, and how did that imprint upon us?

In a recent study put out by the Center for Health and Well-being at Princeton University, Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman and Angus Deaton have reviewed the responses of 450,000 Americans and concluded that there is a direct correlation between money and some forms of happiness, at certain income levels.

In seeking a possible correlation between money and well-being the authors sought first to differentiate between two forms of happiness – “emotional well-being” and “life evaluation” – and then to plot income levels against these determinants. (Emotional well-being refers to the qualify of an individual’s everyday experiences. Life evaluation relates to the thoughts people have about their life when they think about it, i.e. “How satisfied am I with my life?”

The authors observed striking differences in the relationship of these two forms of well-being to income level. The bottom line? Not unexpectedly, a lack of money can exacerbate the affect of adverse circumstances (divorce; ill-health; loneliness) and interfere with ones ability to be happy. Notably, however, beyond $75,000, higher income is neither the road to happiness nor to the relief of unhappiness. Both varieties of happiness increase with income, but only up to $75,000. Beyond this income level there is no improvement whatsoever in the quality of ones life (emotional well-being) while there is a marked increase in ones over-all sense of success, or life evaluation. (In fact the authors found that the sense of general life satisfaction rises steadily with the rise of income.)

I believe these findings have much to offer us when we think about our money and whether or not it makes a difference in our lives. For individuals below the $75,000 income threshold, it is perhaps a question of finding and using other tools which would act as a counterweight to life’s challenges and soften the affects of adverse circumstances. These include deeper elements such as love of and from family, work contentment and spiritual connection, along with the more nuts and bolts factors such as budgeting, saving, and having the ability to prioritize needs vs. wants vs. wishes. In essence, learning and then mastering the ability to live within ones means.

For people earning more than $75,000, the take away is interesting on several levels. If we are to believe the results of the study, a $75,000 income (per individual) would provide the necessary means for emotional well-being while establishing that anything above this amount does not necessarily make you happier. Indeed, there is some evidence it could make things worse. A recent study in the Journal of Psychological Science (May 18 2010) entitled Money Giveth, Money Taketh Away provided evidence of a possible association between high income and a reduced ability to appreciate small pleasures.

Kahneman and Deaton have postulated that perhaps $75,000 is a threshed beyond which further increases to income no longer improve a persons ability to improve their emotional well being, such as spending time with people they like and enjoying leisure time. The increased ability to “purchase” positive experiences may also be offset by some negative effects common to higher wage earners, including stress, competitiveness, time constraints, high expectations and time away from family.

The lesson for me and for my clients is simple, in concept at least: become active in the exploration and discovery of what contributes to your well-being (both the simple and the profound) and then look for the connections that your money has to these things. I have worked with many clients who at one time or another experienced blocks in deploying their money towards enjoyable experiences that would have impacted upon their well-being. There is no easy explanation for these blocks, but through a bit of effort and planning they can be discovered, and conquered.

Money may not buy happiness entirely, but the money each of us has does have the potential to provide sustained well-being. The more planning and intent we apply to how we use our money and how that impacts upon our daily lives, the “happier” we will be. It is an effort worth undertaking.

Values-Based Financial Planning

September 1, 2010

Say the word “financial advisor” and take note of the images that appear in your mind: stockbroker in a skyscraper? Salesperson behind a desk? Insurance agent with a coat and tie? The person who does your taxes? Someone who sold you a mutual fund? Perhaps an actor in a television commercial?

Our notions about financial professionals are generally based on the personal experiences we have had with them. For this reason, one of the first things that I ask of prospective new clients is to share with me the experiences they have had with past advisors. What this usually leads to is an opportunity to differentiate the types of financial advisors populating the industry, while also providing a chance for clients to express their ideas about the kind of advisor they would like to work with.

Although Registered Investment Advisors (of which I am one) and Registered Representatives of large brokerage firms (which I used to be) are heavily regulated, the practice of financial planning is largely free of institutional oversight. This is because financial planning is less about what we are and more about what we do.

In short, Registered Investment Advisors who are also financial planning professionals can differentiate themselves quite easily: we are fiduciary advisors, meaning we have an obligation to put the interests of our clients ahead of our own. In order to appreciate this distinction, it helps to understand that employees of broker-dealer firms typically act under “suitability” guidelines, meaning their only obligation is to recommend what is suitable for the client, even if it also happens to pay them the biggest commission.

So, while there are many licensing bodies and trade organizations that financial planning professionals belong to, the lack of an actual regulatory structure which governs how we define ourselves lends itself to a sort of entrepreneurialism and branding that, as long as we are not running afoul of the Securities and Exchange commission or the National Association of Securities Dealers, is perfectly “kosher.”

This blog, of which this entry is the first, will promote topics which place our firm, Milestone Financial Advisors, within a small niche of fee-only advisors known to ourselves (and our clients) as financial life planners, AKA humanistic financial advisors, AKA holistic financial advisors. Behind these monikers is the notion that there is more to financial planning than the nuts and bolts tools which seek to answer questions such as “When can I retire?” or, “How much is enough?” or, “How much will I have to save to send my kids (or grandkids) to college?” Certainly, values-based planners address these issues and utilize these tools, but not before a process of exploration and discovery that seeks to understand our clients most essential life goals. Without such knowledge, how can we possibly hope to answer these questions when the definitions of “retirement,” “security” and “wealth” and “benevolence” are so individual?

Within this niche, our professional goal is to enhance the quality of our clients lives by creating financial plans that integrate their investments with the broader elements of their lives. We seek to create a supportive framework for helping identify and prioritize our clients most meaningful financial goals; in short, to help them place their money into alignment with their values.

We hope you will return to this blog for news, insights and information that supports all of the above.

Thanks for reading.